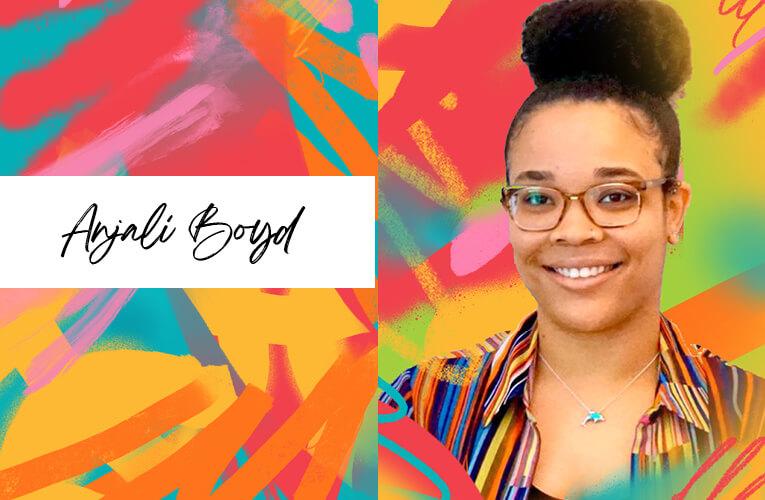

You may remember Anjali Boyd as the Nicholas School student and community advocate who surprised the political establishment by running for district supervisor of the Durham County Soil & Water Conservation District in 2020, and winning.

Her double-digit victory over four other candidates in the race, her first run ever for public office, served notice that she’s someone to watch.

Now, she’s exceeding expectations again.

This January, the National Academy of Sciences appointed Boyd, a first-year doctoral student in marine science and conservation, to serve as an early career liaison on the U.S. National Committee for the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development.

As the only student and youngest member selected to serve on the committee, she’s helping guide its efforts to broaden the ocean science tent and inspire more young people, especially women and students of color, to pursue careers in the field.

In concert with that work, this February Boyd launched The Hub, a national online database that connects students with funding and internship opportunities in marine science, biodiversity and other environmentally focused STEM fields.

As a Black woman in marine science, which is one of the least racially diverse STEM fields, it has always been important for me to create spaces and opportunities for other students of color to explore STEM fields and learn about the various career opportunities available to them."

–Anjali Boyd

Closer to home, she’s helped develop new K-12 STEM curriculum for the Duke Marine Lab’s Community Science Initiative, and launched the Durham Youth Contest, a program that awards seed grants of up to $500 to support youth-led community-based conservation.

Boyd has also helped spearhead iNviTECH, an educational outreach initiative that aims to engage the next generation of STEM innovators and unlock their entrepreneurial spirit through specially designed, age-appropriate programs – the iNviTECH Playschool, Clubhouse and iLab – for preschool and K-12 children of color.

“As a Black woman in marine science, which is one of the least racially diverse STEM fields, it has always been important for me to create spaces and opportunities for other students of color to explore STEM fields and learn about the various career opportunities available to them,” she said.

Born and raised in Durham in a family that placed high values on academic excellence and community service, Boyd was drawn to a career in marine science after taking a course in high school and becoming “fascinated with learning about this unknown and unfamiliar world.”

As an undergraduate at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Fla., she immersed herself in the ocean science and policy world, augmenting her coursework in marine biology with internships at NGOs and leadership roles in student chapters of the Ecological Society of America (ESA) and other scientific organizations. She also made time to share her love of science and nature with local K-12 students by serving as a volunteer STEM mentor and tutor through Eckerd’s Office of Service Learning.

Those experiences confirmed for Boyd that marine science and education are where her passions lie, but they also drove home the need for more diverse representation in the environmental field.

That realization was one of her chief motivations for running for elected office after returning home to Durham to pursue doctoral studies at the Nicholas School.

“There are currently more than 450 Soil & Water Supervisors across North Carolina, but only three of us are Black women,” Boyd said. “This means there’s an entire lens we’re not using when designing and implementing conservation solutions.

“For years, environmental conservation organizations have lacked diversity and reinforced systems of inequalities. It’s essential that we correct these wrongs of history to ensure that Black and Brown communities, like the one I grew up in, have equitable access to clean natural resources and a say in how they’re managed.”

Today, in addition to her Soil & Water Conservation District duties and her National Academy committee work, Boyd remains actively engaged with ESA, the Society of Wetland Scientists and other national scientific organizations to boost underrepresented minority participation in ocean science and conservation.

Last September she was appointed by ESA’s governing board to serve on the 9,000-member association’s Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Justice Task Force. She is the youngest member and only student on the task force.

She’s also working to help launch a new organization, Black Women in Ecology, Evolution and Marine Sciences that aims to “rewrite the narrative and drive innovation.”

Boyd’s list of research achievements is just as impressive.

In 2018, while still an undergraduate at Eckerd College, she was named a NOAA Hollings Scholar and subsequently spent four months conducting research on seagrass and food web ecology at the Duke University Marine Lab, under the guidance of faculty member Brian Silliman. That work led to her receiving an honorable mention in the highly competitive National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship program in 2019 – before she was, technically, even a graduate student.

In 2020, Boyd received a Dean’s Graduate Fellowship to pursue doctoral studies at the Nicholas School, where she is a member of Silliman’s lab. She is already lead author of one peer-reviewed study, now in review, and another that she hopes to submit for publication this year. Her work focuses on testing the hypothesis that removing top predators in a marine ecosystem will result in an increased abundance of mid-sized predators, or mesopredators, which, in turn, will lead to a decreased abundance of smaller prey species—essentially throwing the marine food web out of balance.

Understanding the implications of these interactions and how they may be exacerbated by physical pressures like erosion or sea-level rise is essential for reversing the loss of saltmarshes, seagrass beds, oyster reefs and other marine habitats that are now in decline in much of the world, Boyd explains.

Though still in its early phase, she hopes her work will ultimately contribute to ecosystem-based solutions that boost restoration efforts and help turn the tide of habitat loss. “That’s definitely one of the top things I’m working to achieve, right up there with increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the aquatic sciences, bridging the gap between entrepreneurship and scientific research, and owning and leading my own marine research center,” she said.

Some people might say she’s overly ambitious. But Boyd isn’t buying that.

“It’s about protecting our planet, elevating the voices of youth, people of color and woman, and bringing new perspectives and solutions to the table to address the world’s most pressing environmental and human health issues,” she said. “If you want it to happen, you have to work for it.”