People who experience the impacts of hurricanes, flooding or other severe weather events are often more likely to believe in, and be concerned about, climate change in the wake of the disaster.

But a study co-led by Elizabeth Albright, assistant professor of the practice of environmental science and policy methods, finds that not all severe weather impacts have the same effect.

“How our community or neighborhood fares –- the damages it suffers –- may have a stronger and more lasting effect on our climate beliefs than individual impacts do,” said Albright.

People who perceived that damage had occurred at a broad scale were more likely to believe that climate change is a problem and is causing harm, she explained. They were also more likely to perceive a greater risk of future flooding in their community.

In contrast, individual losses such as damage to one’s own house appeared to have a negligible long-term impact on climate change beliefs and perceptions of future risks.

“These findings speak to the power of collective experiences and suggest that how the impacts from extreme weather are conceptualized, measured and shared matters greatly in terms of influencing individual beliefs,” said Deserai Crow, associate professor of public affairs at the University of Colorado at Denver, who coauthored the study with Albright. Crow earned her doctoral degree from the Nicholas School in 2008.

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation and published in the journal Climatic Change.

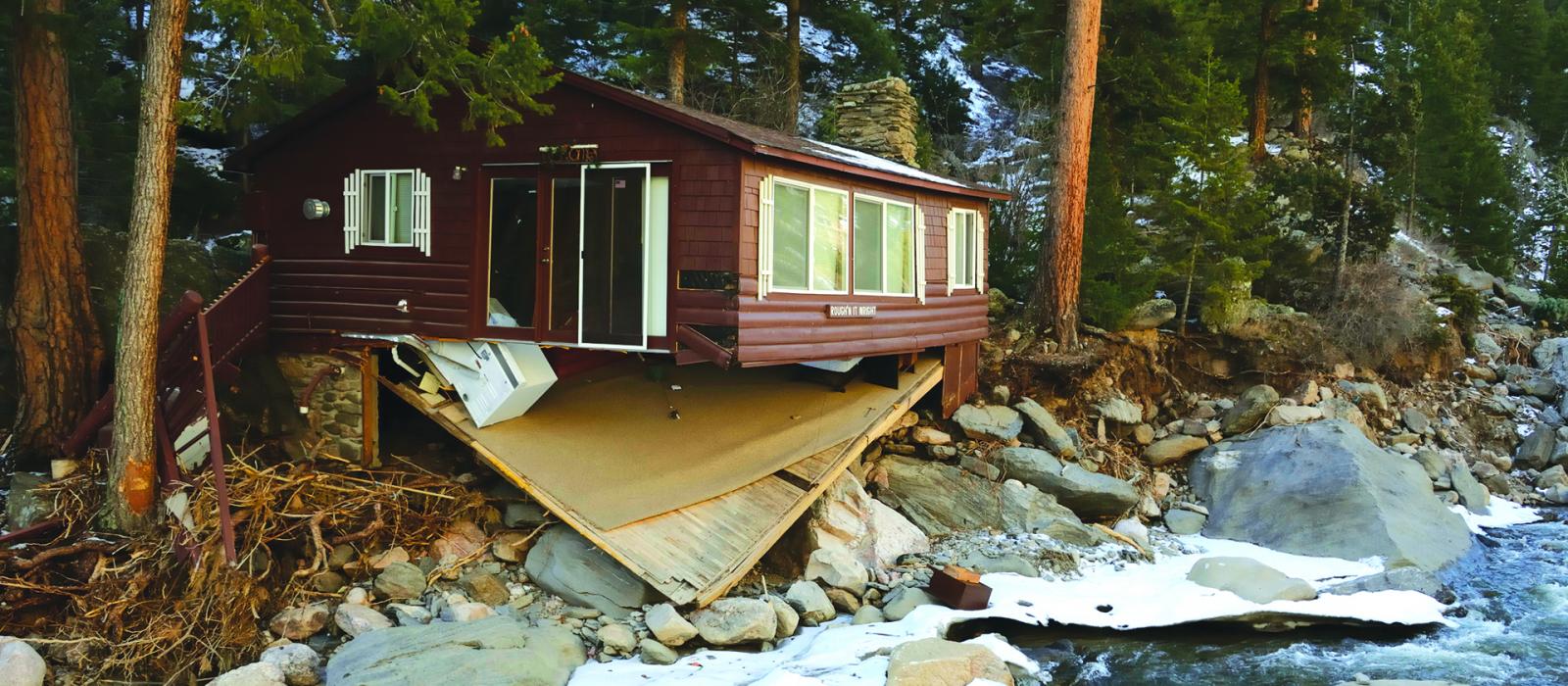

Albright and Crow surveyed residents of six Colorado communities that had suffered devastating flooding after days of intense rainfall dropped nearly a year’s worth of precipitation in mountains upstream from them in September, 2013.

The surveys queried residents about their climate change beliefs, their perception of the extent of damage caused by the flooding, and their perception of future flood risks in their neighborhood. It also asked for personal information, such as political affiliation.

“As expected, we found that political affiliation was related to the extent to which flood experience affected a person’s climate beliefs,” said Crow.

This partisan divide did not extend to perceptions of future floods risks though, she noted. Republicans and Democrats perceived similar levels of risk, regardless of whether or not they attributed it to human-caused climate change.

“It’s important that we understand these differences and commonalities if we want to build back better and more resiliently after a severe weather disaster,” Albright said.