Tim Lucas

(919) 613-8084

tdlucas@duke.edu

This is the fifth in a series of six stories on the NSOE’s inaugural faculty research symposium at the Marine Lab, in Beaufort, on September 29th.

Juliet Wong, assistant professor of coastal and marine climate change, is a global-change biologist, specifically interested in how climate change affects marine ecosystems and their organisms, working to predict biological responses for improved resilience to adverse environmental events.

Having newly arrived at the Duke Marine Lab in August, Wong presented “Organismal Responses to Climate Change in the Sea” at the symposium, describing several ongoing studies on coastal marine invertebrates. Using molecular and physiological approaches, her work seeks to identify adaptive responses to climate change and to examine the mechanisms underlying those responses.

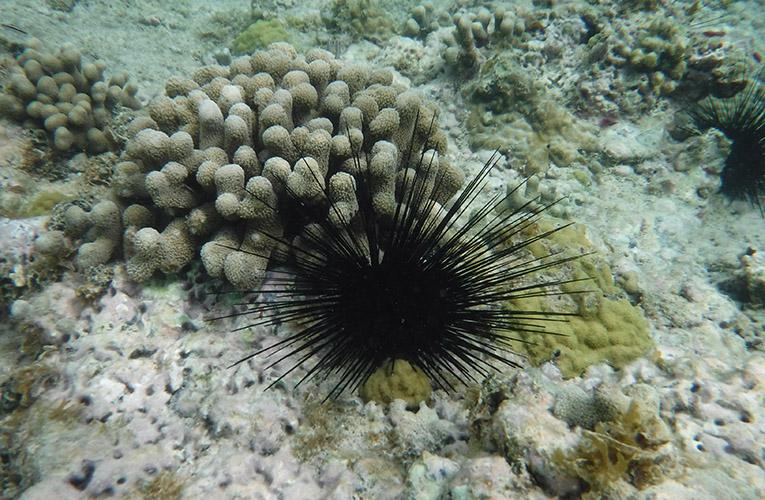

Wong’s talk focused in part on the long-spined sea urchin Diadema antillarum, found largely in the western Atlantic on Caribbean coastal reefs, and the related management of coral reef ecosystems in Puerto Rico. The urchins graze on macroalgae living in competition with the coral; the urchins’ good health benefits the health of the reef; without them, algae smothers the coral. Diadema had been the most prevalent herbivore in the Caribbean, constituting an important part of the food chain until a mass die-off in the early 1980s that went largely unexplained. Over the ensuing years, coral-dominated reefs became algae-dominated reefs; at the same time, the Diadema were slowly recovering.

In 2022, with collection permits in hand and a plan to observe Diadema populations across coastal reefs in Puerto Rico, Wong found herself in the midst of a field study whose parameters were being unexpectedly dictated by the study’s species itself: another mass mortality event, forty years after the one that devastated Diadema antillarum in 1983.

First observed in the U.S. Virgin Islands, the die-off of Diadema was later attributed to infection by a scuticociliate, a protist whose attack leaves an urchin unable to defend itself from predators, to shed spines and quickly succumb, according to researchers at Cornell led by Dr. Ian Hewson. Wong changed her original plan, tracking the event as it spread westward, from Puerto Rico’s island of Culebra to the northern coast of the main island of Puerto Rico. Hurricane Fiona, a category-4 storm that made landfall in Puerto Rico that September, likely further accelerated Diadema decline. It was an accommodation made by necessity, as the populations dwindled over ongoing months, which Wong described as devastating, referring not only to the numbers. “It was sad to witness in person,” she said, and yet, this experience may have provided the best hope for understanding recovery.

Wong’s subsequent research, which includes analysis of sea urchins, observation of righting-response time — how long it takes an upended urchin to reorient its position — and DNA analysis, indicates that the disease may affect the urchins’ water vascular systems. Healthy urchins are sensitive to light and can respond to moving shadows: “They will move and orient their spines to point them at you,” she said. Higher loads of the scuticociliate pathogen, determined by droplet-digital PCR (ddPCR) analysis, meant slower or no response times; sick urchins are more at risk of being eaten by predators.

Working with colleagues on sequencing the Diadema genome, Wong is also studying the urchins’ responses at the molecular level, and whether gene expression influences fitness. While population densities have remained low in many areas of Puerto Rico, the past year yielded a surprising development: a population rebound at Punta Escambrón in San Juan.

She also described an ongoing project funded by Puerto Rico Sea Grant. This collaboration, with Dr. Jose Eirin-Lopez of Florida International University, and Dr. Alex E. Mercado-Molina of Sociedad Ambiente Marino (SAM), a nonprofit, community-based organization dedicated to marine reef-restoration and coral reef management, is currently investigating how water quality and climate change are driving the success of Diadema across reefs. In the spring, sea urchins will be relocated to new reefs in an effort to determine which genotypes or epigenotypes may be better suited to suboptimal conditions.

Wong has now spent time on several varied coasts, even going back to childhood days fishing for sea bass and barracuda with her father, off southern California. The marine ecology in Beaufort presents new opportunities for her research: work with aquaculture scientists, oyster farmers, and Duke colleagues to study the Eastern oyster; and comparative studies of the Atlantic-native sea urchin Lytechinus variegatus, whose genome has already been sequenced by Duke’s Department of Biology. She’ll also continue to explore how environmental conditions can affect marine animals across multiple generations, from parents to their offspring, all leading to a better understanding of organismal responses to environmental stress and how to promote higher resilience to climate change.