Nicholas School Communications & Marketing

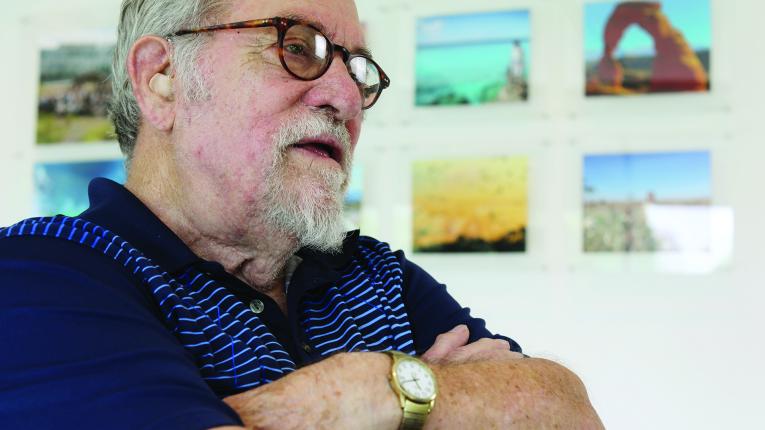

DURHAM, N.C. — Orrin Hendren Pilkey, the widely cited, outspoken Duke University coastal geologist and beloved professor whose influence could move lighthouses, and whom The New York Times once described as the “reigning dean of American coastal studies,” died on Dec. 13 at the Croasdaile Village retirement community in Durham. He was 90.

His daughter confirmed that the death was of natural causes.

Pilkey, James B. Duke Professor Emeritus of Geology at the Nicholas School of the Environment, had been on Duke’s faculty since 1965, with year-long stints at the Department of Marine Science at the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, and the U.S. Geological Survey in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. He also founded and was director emeritus of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines.

A prolific researcher and writer, Pilkey published more than 250 scientific papers, various op-eds and 49 books on topics such as barrier islands, coastal erosion and sea level rise. He also co-edited and co-wrote Living with the Shore, a 22-volume series about the hazards of beachfront living.

Pilkey’s research, as well as his impassioned participation in hundreds of town hall meetings, legislative hearings, news stories and public debates, helped shed light on the dynamic nature of barrier island geology, the threat of sea level rise and the need for sustainable development in ecologically fragile coastal environments.

“He had very strong views,” said Norman Christensen, founding dean of the Nicholas School. “He would talk about them anywhere. But he could also talk to people he didn’t agree with in a way that was cordial. [He had] a sense of humor [such] that even people who vehemently disagreed with him still couldn’t help but like him.”

Early Years at Duke

Born in New York City on Sept. 19, 1934, Pilkey spent most of his childhood in Richland, Washington, where his father worked as an engineer at the Hanford plutonium plant.

Pilkey earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in geology from Washington State College and the University of Montana in 1957 and 1959, respectively, and a doctoral degree in geology from Florida State University in 1962. Between college and graduate school, he served a term in the U.S. Army, “where the most important thing I learned was how to behave when someone orders you to do something irrational,” he told Duke in 2019.

Between 1962 and 1965, Pilkey was a research professor at the University of Georgia Marine Institute on Sapelo Island. Wooed by the promise of doing research aboard Duke’s new vessel Eastward, Pilkey joined the Geology Department, initially focusing on how sediment transported by powerful currents shapes abyssal plains — stretches of seafloor that plunge to murky depths of 10,000 to 21,000 feet.

“His early research involved studying turbidite deposits, which much of the deep sea floor consists of — rocks that are laid down by these amazing flows that nobody knew about before the middle of the last century,” said geomorphologist A. Brad Murray, director of graduate studies for the Nicholas School’s Earth and Climate Sciences Division. “Orrin helped discover their origins and how widespread they were by going out and pulling up bits of the sea floor and interpreting what they were, and made a very famous name that way.”

Pilkey’s focus shifted after August 1969, when Hurricane Camille — a devastating category-5 storm — swept across the Mississippi Gulf Coast, flooding the house where his parents then lived.

“It was my ‘a-ha’ moment,” he told Duke. “The destructive power of that storm made me realize I could apply my expertise on sediment transport to something that could make a real difference in the lives of millions.”

A Voice for Science

In the decades to follow, Pilkey was dedicated to educating the public and decision makers about coastal management, particularly the economic and ecological shortcomings of trying to stabilize eroding shorelines through beach replenishment or seawalls and other hardened structures.

“I think his great legacy will be reminding us that barrier islands are not static features of our coasts. They’re continually moving,” said Andrew Read, director of the Duke Marine Lab. “And if we don’t want them to move because we build on them, then we’re going to have to be continually trying to stop them from moving by engineering. And that’s a battle — Orrin would say — we are destined to lose.”

In 1986, Pilkey founded the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Duke as a vehicle for translating science about coastal processes and geologic hazards for decision makers involved in coastal management.

“Science needs a voice. We need to share what we know, and that’s what I try to do,” Pilkey told Duke. “These beaches don’t belong to the people who have chosen to build structures there. They belong to our children and grandchildren. What a tragedy it would be if we let them be destroyed because we didn’t speak up and share the truth.”

Pilkey’s writings and scientific testimony helped persuade the North Carolina Coastal Resources Commission in 1985 to prohibit the use of most seawalls and other hardened structures on the state’s coast, with South Carolina following suit in 1988.

Pilkey’s doggedness also helped set the ball rolling for a major feat of engineering: moving the iconic Cape Hatteras Lighthouse — a 198-foot, black-and-white structure built in 1870 — inland 2,900 feet from its original site on the barrier island, where erosion threatened its foundation. Despite pushback, an independent study endorsed the relocation, which occurred in 1999.

“He epitomized the kind of approach that we try and emulate at the Nicholas School and at Duke broadly: science in service to society,” said Pilkey’s former Ph.D. student Rob Young, director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines, now based at Western Carolina University. “He did great science, but boy, he was a passionate and articulate and effective advocate to make people think about what was going to happen to our beaches, especially later on, to what will happen to our beaches with climate change and sea level rise.”

Indeed, Pilkey was a vocal critic of legislation passed into law in North Carolina in 2012 that prevented state planning agencies from taking any action based on projected sea level rise until 2016.

“It’s time to leave the beach, at least in terms of having permanent structures and communities there. The seas are rising. Storms are intensifying. We need to begin an orderly retreat while we still have time,” Pilkey told Duke.

“Even after retirement, Orrin never stopped working on issues he cared about,” said Lori Bennear, interim Stanback dean of the Nicholas School. “He was just in my office earlier this fall delivering his latest book, Escaping Nature: How to Survive Global Climate Change.”

Colleague, Mentor, Friend

Pilkey was a widely respected colleague, mentor and friend whose dedication, sense of humor and self-deprecation drew people in.

“I always claimed that Orrin was instrumental in a couple of factors, and basically saved my life,” said oceanographer and Nicholas School adjunct faculty member Philip “Flip” Froelich.

As a Duke undergraduate floundering in chemistry classes, Froelich sought guidance in Pilkey. Pilkey took him under his wing, recommending Froelich enroll in oceanography classes at the Marine Lab and later hiring him to assist with research in Puerto Rico.

“He got me on that chemical oceanography cruise and essentially turned me into a marine chemist,” Froelich said.

Emily Klein, who joined the Duke Geology Department in 1989 as its first female faculty member, recalled Pilkey’s warmth and encouragement in what was at the time a male-dominated field.

“More than anyone, Orrin was totally comfortable with having the first woman in the department,” she said. “He believed in me and brought me into his family — his scientific family, as well as his personal family — and made me feel completely welcome as part of his thriving community — a community that was rich and active and exciting.”

“He created both the physical space and the emotional space to weave together a community of people that cared about each other and supported each other and helped us do our science and live our lives to the fullest,” she added.

Young echoed the sentiment, noting that Pilkey, wife Sharlene, and their five children opened their home to students and faculty alike.

“The doors were literally never locked. I mean literally,” Young said. “There were times when I’d be driving by there — and this is after I graduated — and would stop by to see the Pilkeys, and they weren’t there, but I’d go inside anyway and make lunch.”

Meanwhile, Pilkey’s popular winter field course, which took students to undeveloped Shackleford Banks to study coastal processes, was the stuff of legend.

“It was a combination of marching through either cold wind and beach sand or dense maritime forests on paths that only Orrin seemed to know,” said Murray, who has continued the field trip tradition with his students at the Nicholas School. “Orrin was really, really fun to be out there with, and also really engaging for the students.”

Rightful Recognition

In 2007, the North Carolina Coastal Federation awarded Pilkey a Lifetime Achievement Award in recognition of his tireless advocacy to convince the N.C. General Assembly to enact the state’s landmark Coastal Area Management Act of 1974, which regulated development in coastal areas, and the ban on hardened structures along the oceanfront, formally adopted into law in 2003.

Pilkey’s long list of professional honors also included the Geological Society of America’s GSA Public Service Award in 2000; the James H. Shea Award for Excellence in Earth Science Writing and Editing, from the National Association of Geoscience Teachers in 1993; and the Francis P. Shepard Medal for Excellence in Marine Geology in 1987, among others.

In 2014, the Duke Marine Lab honored him by dedicating its newest research building as the Orrin Pilkey Research Laboratory.

“Orrin is certainly among the most memorable people I ever worked with. He’ll be greatly missed,” said Christensen. “Reflecting on his life, we should all have the privilege of having the impact that he did.”

Pilkey is survived by his children Charles Pilkey, Diane Pilkey, Keith Pilkey, Kerry Pilkey and Linda Pilkey-Jarvis; six grandchildren; and one great-granddaughter. He was preceded in death by his wife, Sharlene Pilkey, née Greenae; brother Walter Pilkey; and a grandson.

###