Cindy Van Dover

Setting Safeguards for Deep-Sea Mining

As an expert on chemosynthetic ecosystems that exist thousands of feet beneath the ocean surface, and as the first woman and PhD scientist to pilot the deep-sea research submersible Alvin, Cindy Van Dover knows firsthand how fragile life is on the ocean floor.

She also knows that industrial mining of minerals and other resources found there is inevitable.

So, in 2018, Van Dover joined with colleagues from 16 institutions to issue a peer-reviewed framework of 18 safeguards that could be implemented to protect biodiversity near sites where mining will occur and identify areas of special ecological importance that should be labeled off-limits.

Though it’s too soon to know what effect the framework will have, it was important to put forth the safeguards before industrial-scale mining begins because deep-sea ecosystems and species can take decades or even centuries to recover from a disturbance, if they recover at all, says Van Dover, Harvey W. Smith Professor of Biological Oceanography.

“We could either sit on our hands and worry, or we could do something,” Van Dover says of the paper’s authors, which included fellow Nicholas School faculty members Daniel Dunn and Patrick Halpin. “We opted to do something.”

Curt Richardson

The Swamp Doctor

From the Everglades to the Mesopotamian marshes and the peatlands of eastern North Carolina, Curt Richardson knows a thing or two about how to restore a degraded wetland.

His meticulously executed field studies, conducted over a 14-year period from 1989 to 2003, helped establish new standards for the release of phosphorus-laden runoff from nearby farms and homes, into the nutrient-sensitive Everglades, and also helped curb the harmful impacts of reduced water flow, caused by the over-use of the local aquifer for irrigation.

In Iraq, Richardson’s expertise helped international agencies assess the restoration potential of the famed Mesopotamian marshes—possibly the inspiration for the Bible’s Garden of Eden—after large swaths of the swamps were drained or destroyed during the 2003 war.

Closer to home, Richardson, director of the Duke Wetland Center, is working to restore eastern North Carolina’s pocosin peatlands and explore their potential for long-term carbon storage. His research suggests that when fully restored, these bogs, many of which were drained for agriculture decades ago, could store 10 to 15 times as much carbon as unrestored lands. He’s testing that premise at the new 10,000-acre Duke Carbon Farm.

Brian Silliman

Predatory Behavior

Could rethinking our long-held assumptions about where animal predators "belong" be a key to ecosystem restoration?

John Poulsen

Poulsen vs Poachers

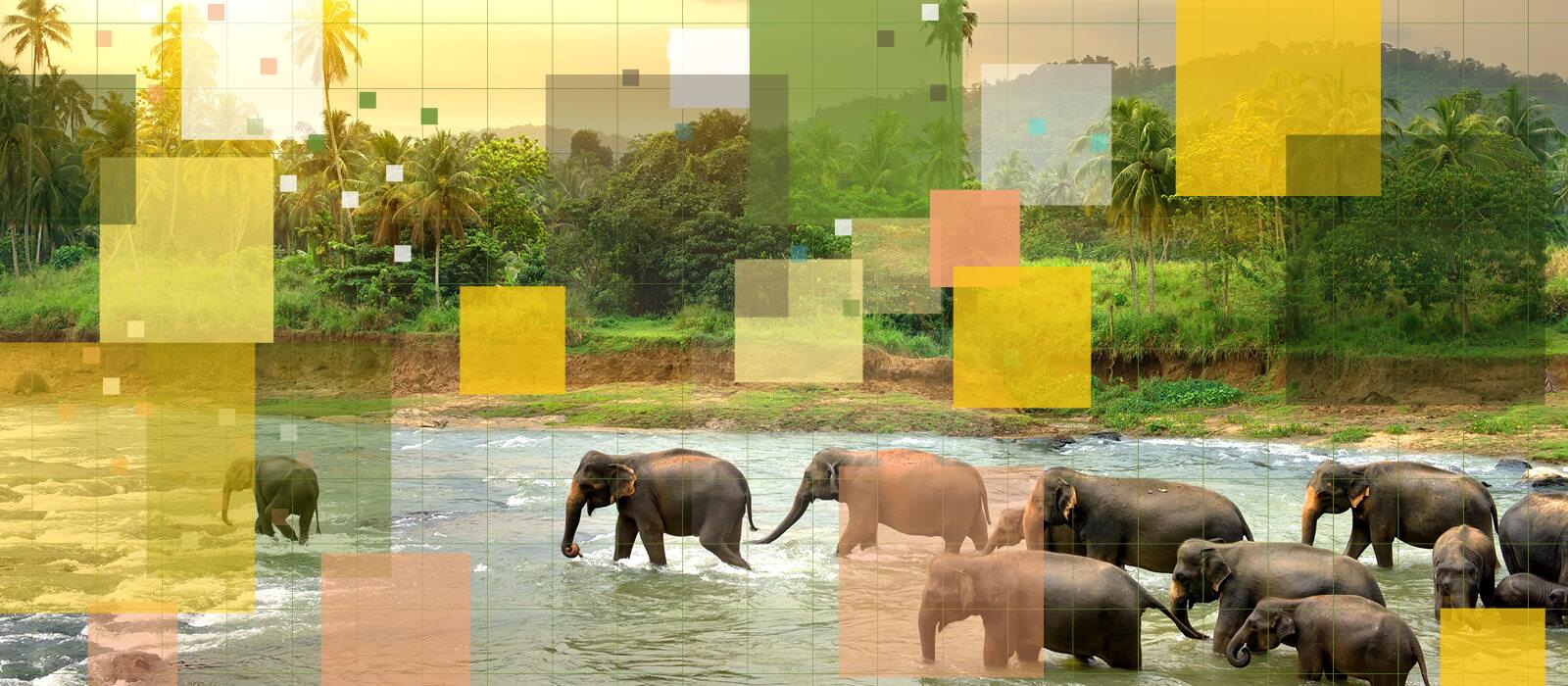

The international black market in ivory has exacted a terrible toll on forest elephants in Central Africa.

Estimates suggest more than 25,000 elephants, or about one-quarter of the region’s total population, have been slaughtered for their ivory since 2004. Pachyderm populations in Gabon’s Minkébé National Park, one of the region’s most important preserves, have declined by about 80% due to the combined impacts of poaching and habitat loss.

John Poulsen, associate professor of tropical ecology, is working to reverse these declines.

Poulsen’s research, often conducted in partnership with the Gabonese government, local conservationists, park rangers and landowners, has yielded the most reliable estimates to date of the staggering scope of the losses. It’s also provided new insights into the pivotal role forest elephants play in maintaining the structure and composition of Central African forests; how those forests might change if the elephants disappear; and what humans can do to help reduce the threats posed by both poaching and habitat encroachment.

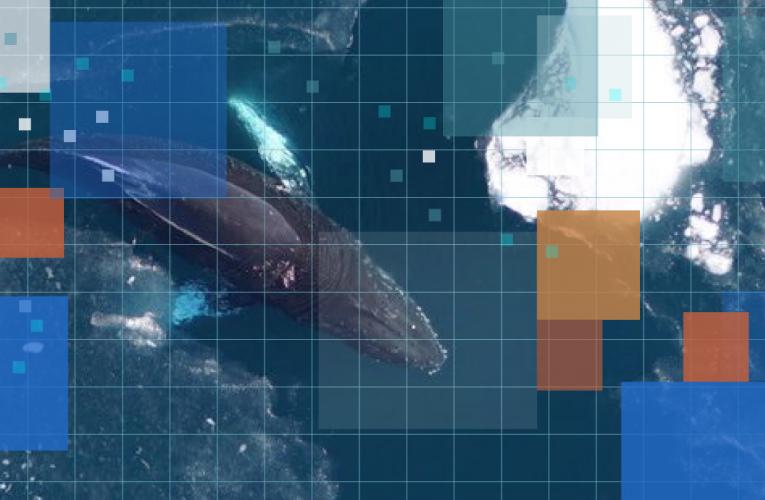

Andy Read + Doug Nowacek + Dave Johnston

The Marine Mammal Dream Team

Take one guy who’s a world-class expert on the effects of human activities on marine vertebrates, one who’s a leading innovator in bioacoustics and conservation technology, and one who’s a brilliant gearhead and marine ecologist, and what do you get?

Andy Read, Doug Nowacek and Dave Johnston: The Duke Marine Lab’s “Marine Mammal Dream Team.”

With more than 400 peer-reviewed papers between them, Read, Nowacek and Johnston have helped establish Duke as a hub for cutting-edge marine mammal research, with an emphasis on the development and use of new conservation technologies.

Their far-ranging research has helped shed new light on a wide array of critical conservation issues, including how migratory marine mammals and other sea life are affected by underwater noise pollution; the effects of microplastics on marine ecosystems; and the effects of climate change on critical humpback whale foraging grounds along the Western Antarctic Peninsula.

Read is Stephen A. Toth Professor of Marine Biology. Nowacek is Repass-Rodgers University Distinguished Professor of Conservation Technology. Johnston is associate professor of the practice of marine conservation ecology and director of the Duke Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab.

John Terborgh

Top Down or Bottom Up?

In ecology circles, few questions spur more spirited debate than whether top-down or bottom-up processes are more important for maintaining species diversity in an ecosystem.

On one side, you have the bottom-up camp who believe that primary producers low in the food web, such as plants, hold the key because if their numbers shrink, the effects trigger declines among the herbivores that eat them and, eventually, among carnivores who now have fewer herbivores to eat.

On the other side, you have the top-down crowd, who believe predators at the top of the food web exert greater control.

In 2015, professor emeritus John Terborgh, one of the most influential tropical ecologists of his generation, entered the fray with an erudite—and instantly disputed—peer-reviewed article that makes a compelling case for the top-down theory.

Bottom-up approaches have failed to yield a consensus theory, he argued, while top-down control has been shown to promote diversity in a wide range of ecosystems, including rocky intertidal shelves, coral reefs, the nearshore ocean, streams, lakes, temperate and tropical forests, and arctic tundra. “Diversity is maintained by the interaction between predation and competition,” he wrote. “Strong top-down forcing reduces competition, allowing coexistence.”

Read more stories featured in the Duke Environment Magazine Fall 2021: 30th Anniversary Issue.

Tim Lucas

(919) 613-8084

tdlucas@duke.edu